History

Materials

Before lace made from linen thread, the technique was used to make ribbons from wool, silk and metallic thread. In Europe, the Renaissance, which began in the 16th century, gave birth to a new garment. The linen undershirt was created as a way to protect expensive and difficult-to-clean outer garments. The collars and cuffs of the undershirt began to be decorated with lace made with white linen thread. The lace stood out beautifully against the darker outer garments. The art of lace-making spread rapidly from Italy to France, the Netherlands and the rest of Europe and lace became an important part of international fashion.

The impact of different styles

Lace styles followed with a delay the stylistic trends in art:

- Renaissance lace: 1500s.

The patterns of the lace are reminiscent of a spider’s web. - Baroque lace: 1600s. The lace is wide and full of intricate, clear-cut floral patterns.

- Rococo lace: 1700s. Lace culture flourished in Europe and the lace trade became very profitable. The height of the Raumalace industry was in the rococo period. The rococo period saw the beginning of the reign of the base lace, during which a base mesh was woven between and connecting the lace patterns.

- Neoclassical lace: the end of the 1700s saw the last phase of the lace styles. Many of the handkerchief lace made in Rauma belongs to the neoclassical lace. With the French Revolution, lace was no longer worn by the nobility.

Raumalace

The earliest lace came to Finland in the 16th century with merchants. There are various theories about the origin of Raumalace, but the most likely theory is that lace and the art of skinning were brought here by merchant shipping. In Rauma, lace begins to appear in family records from the 17th century onwards.

There is evidence that lace-making has been practised in Rauma since at least the 17th century. At the end of the 17th century, 200-300 of the approximately 1500 inhabitants of Rauma earned their living by making lace. Almost every household was involved in lace-making. There were lace-makers of all ages, women, children and old men.

Unlike the big European lace manufacturing hubs in Belgium and France, lace-making never developed into an industry in Rauma, but retained its domestic feel. The Swedish-Finnish Manufactory Council – the Ministry of Economic Affairs at the time – did not consider homemade handicrafts to be an industry, even if the products had a wide market.

Central European lace-makers were taught in lace-making schools run by lace merchants. They made fashionable patterns designed by the merchants from high-quality threads, produced with the specific requirements of the lace-making process in mind from the time the flax was grown. In Rauma, on the other hand, the threads used by the lace-makers were often of poor quality and the designs, or mynsteris, were often made directly from the finished piece of lace, resulting in an uneven result. However, Rauma is the only place in Finland where professional lace-making has been practised.

The golden age of Raumalace

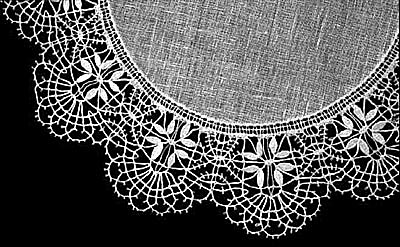

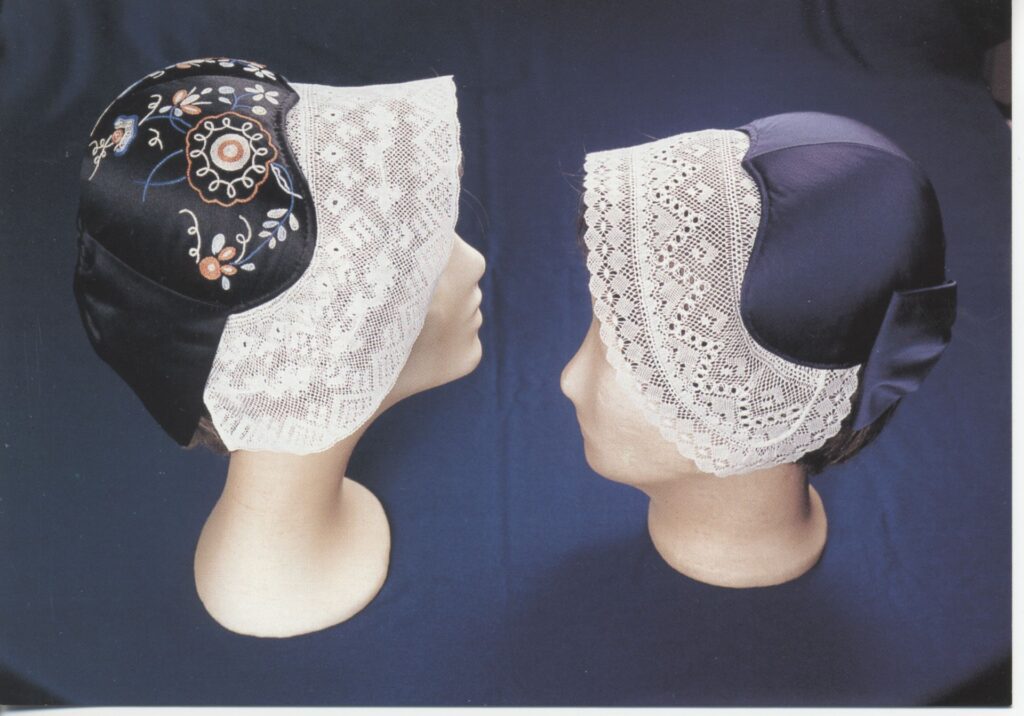

From the late 1700s to the 1840s was the heyday of Raumalace. This period was the fashionable period of the tykkimyssy (French hood), and wide lace was embroidered on the hoods as decoration. The finest lace for the tykkimyssy made in Finland was made in Rauma and the best lace-makers made only wide lace.

A tykkimyssy is a headdress worn by women at church events and festive occasions. The cap was well looked after and was handed down from generation to generation. The hat consists of a hard bonnet, usually covered with silk, and a ‘tykki’ (from the Swedish word tyg – fabric), which can be fabric, but most often consists of 1-3 strips of lace, the middle of which is a wide base lace.

The most popular lace design for a tykkimyssy is the rococo ‘Frimodiglai’, which is possibly a design that originated in Rauma. Usually the designs were copied from lace imported from abroad. From Rauma, lace for the tykkimyssy was exported to at least Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Russia.

Breakthrough period

Towards the 19th century, the use of lace decreased. From the 1850s onwards, fine lace was replaced by thicker linen embroidery, the designs of which had been obtained from the German Erzgebirge. The traditional designs varied from plaits, diamond-shaped linen stitches, spiders and almonds. By the 1890s, only a few elderly women were capable of making fine lace. From the early 20th century onwards, cheap factory lace began to effectively eat into the market of handmade lace.

From the early 19th century onwards, as public demand dwindled, outside organisations began to subsidise lace-making. The Finnish Economic Society gave Rauma lace-makers the first public awards. In the second half of the 19th century, the handicraft industry circles began to pay attention to lace. In 1875, the first handicrafts exhibition was held, again rewarding lace-makers from Rauma. In 1868, when the Russian Empress, Maria Fedorovna, wife of Alexander III, ordered lace for herself, Raumalace also attracted attention. One of her laces was named Dagmarila after her, as she was born Dagmar, a Danish princess.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Rauma lace-makers got a patron of the arts by the name of Thella Frankenhaeuser, a woman from Helsinki and Viborg. Mrs Frankenhaeuser organised lace exhibitions and sales in Helsinki, and sourced patterns and threads for Rauma from abroad. From the late 1910s onwards, the city of Rauma provided funds to organise lace-making courses. Since 1947, lace-making has been taught at the Rauma Adult Education Centre.

Supplies and technique

The Raumalace is made using a Dutch-style lace-making cushion. In the mid-19th century, an attempt was made to persuade the people of Rauma to use the German “kötsikkä” model, but without success. The patterns, or mynsteris, were originally made on bark or parchment, later on cardboard. When a new piece of lace was obtained from somewhere, it was placed on the base of the mynsteri and the pattern was pricked through the lace with the free hand. As the needle holes became larger in use, the result could be quite asymmetrical. Nowadays, lace is made into precise patterns and, unlike in the past, the corners of the linen are also laced together instead of two straight pieces being sewn together.

The names of lace

A special feature of Raumalace is the names of the lace derived from the Rauma language, which are, at first glance, very peculiar. Lace is usually named after either its pattern or its designer. Examples of lace named after a pattern are Spindeljepyri, Kouknippu and Mandelkranssi. Others are named after the designer, such as Kaisastiinalai and Sabinalai. One of the narrow and delicate border laces has a particularly handsome name, Fiini Kruukko Krääkkä.